The chassis, equipment, styling and practicality of a motorbike are all massively important. But for most riders, the engine plays the biggest part in what makes a bike great.

Whether it’s a wild 215bhp superbike motor like the Aprilia 1100 V-four, a super-flexible fast road bike unit packed with character like the Triumph 675 triple, or even a friendly daily rider like the Honda CB500 parallel twin, motorcycling seems to produce ‘great’ engines on a regular basis.

This top ten covers a wide range of motors from the past couple of decades, from singles and twins through to triples and fours. Each one has made its mark in more than one bike, which is the sign of a really strong design.

Aprilia V4

Fair play to the engineers at Noale: they saw the writing on the wall for big twins early on. While Ducati stuck to its V-twin (with amazing results admittedly) until the late 2010s, Aprilia had begun to move on from its big Rotax-designed V-twin a decade earlier, experimenting with a halfway house in the form of the RS Cube MotoGP bike, with a Cosworth-designed inline triple.

That motor made good power, but the Formula One roots of the design meant it had terrible rideability, and was a flop in MotoGP.

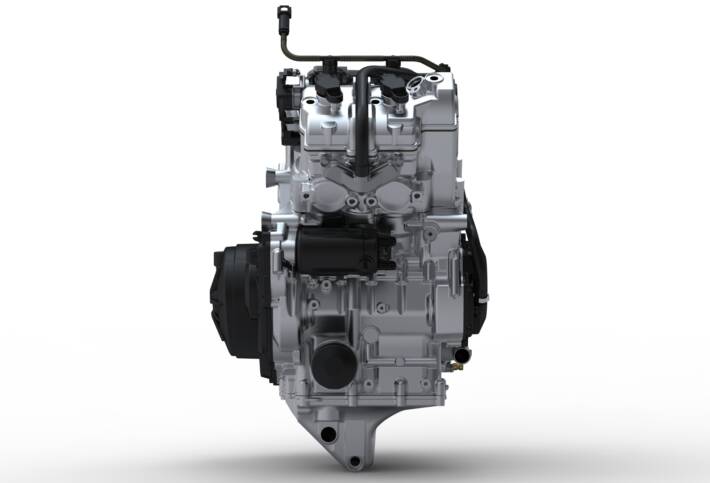

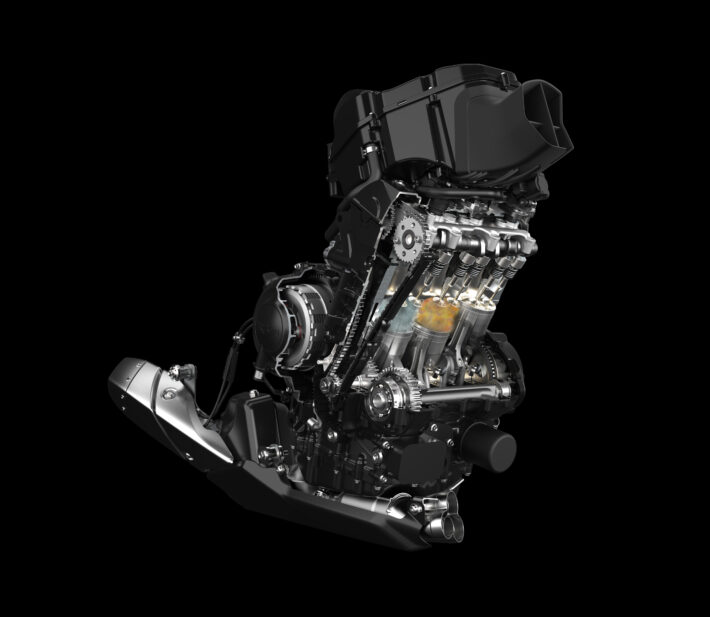

A more positive direction came in the form of a 999cc V-four motor, launched in Rome in 2008 powering the new RSV4 that was aimed at WSBK rather than MotoGP competition. The design was impressive: a 65° V-four, with a balancer shaft, single chain drive to the inlet cam in each head, and a central gear driving the exhaust cams.

Inlet valves were titanium and Nimonic and valve adjustment was by buckets and shims, while the pistons were racing forged designs. At the bottom end, there was a race-style quickly-removable cassette transmission and a mechanical slipper clutch.

Fuelling was by then-novel ride-by-wire fuel injection, and variable inlet trumpets rounded of the high-spec intake system. Peak power was an impressive 180bhp@12,500rpm, with the redline at a heady 14,100rpm.

The RSV4 was a big hit straight off. The super-compact engine design allowed by the 65° layout meant the chassis could be smaller and shorter, with centralised mass. The RSV4 was a struggle for tall riders on the road, but a weapon for racers on track.

And over the next decade and a half, Aprilia first fitted the V4 motor to the Tuono supernaked, then bumped it up in capacity to 1,077cc. Finally, the firm developed the motor into a 1,099cc superbike lump, powering today’s utterly incredible 215bhp RSV4 1100…

BMW Boxer

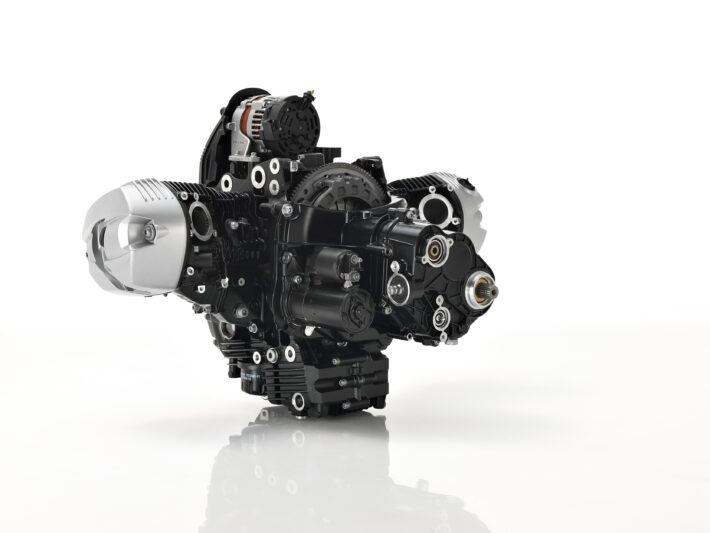

If we’re giving points for dogged dedication, then BMW’s Boxer twin engine must be in with a shout – it’s been making them since 1923! The Boxer layout gets its name from the action of the pistons, which move in and out towards each other, like a boxer’s fists in a fight.

Each piston and conrod runs on its own crankpin, which are 180° out of sync, meaning the cylinders are slightly out of line. Since the pistons move in opposite directions, they balance each other out, though a rocking couple vibration is caused by them being out of line.

BMW’s first Boxer was the M2B15 engine, a version of which powered the 1923 R32, the first BMW motorbike. Since then the firm has always made Boxers (apart from a short period after WW2), and they’ve come a long way in terms of performance.

Up until 1993, BMW’s Boxer twin was a simple air-cooled design, with two pushrod-operated overhead valves per cylinder, and fuelling by one or two carburettors. But the 93 R1100 RS brought in a whole new design, with four-valve heads, fuel injection, and a ‘high-cam’ design.

That used chain-driven camshafts mounted in the side of the cylinder head, and short pushrod/rockers operating the valves. The new engine was oil/air cooled, which gained it the ‘Oilhead’ nickname, and it stuck with BMW’s shaft final drive.

The 21st century saw BMW’s big Boxer grow from an 1100 to a 1200, then 1250, gain DOHC cylinder heads, and from 2019, a new Shiftcam variable valve system. It powers a huge range of bikes, from the R1250 R roadster through the massive-selling R1250 GS adventure bike to the R1250 RS and RT tourers. The old ‘Oilhead’ 1200 is still in production too – used in the hugely popular R nineT range of retro machines.

Ducati Testastretta

Like BMW, Ducati has been inextricably linked with a twin-cylinder motor for decades – but a 90° V-twin, with desmodromic valve operation. The Testastretta is the apex of this design, which powered the firm’s high-end machinery until being usurped by the latest V-four.

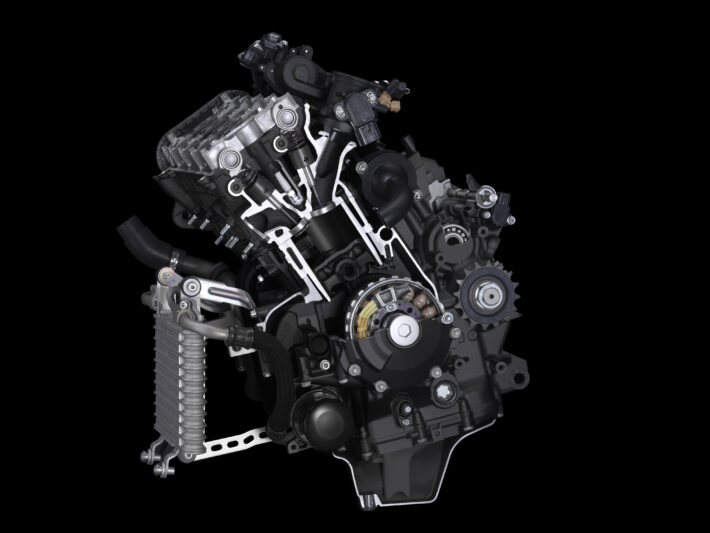

Testastretta means ‘narrow head’, and it refers to the compact design of the cylinder heads on the all-new engine launched by Ducati in the 2001 996R. That engine was a 998cc DOHC eight-valve water-cooled fuel injected design, and made a heady 136bhp: a lot of power back then.

The 996R Testastretta went on to power the 998 and 999 range of superbikes, before being bumped up to 999cc for the 999R homologation special, where it made a beefy 150bhp, thanks to a bigger 104mm bore and shorter 58.8mm stroke.

As always with Ducati, the R models benefited from titanium con rods and valves, forged superlight pistons, aggressive valve timing and large-bore throttle bodies, all to allow high rpm and more power – up to 215bhp on the final motor used in the Panigale 1299 Superleggera. The more basic versions would use cheaper parts, with lower revs and outputs.

Ducati’s flagship V-twins would continue to use motors dubbed ‘Testastretta’, but as they reached 1099, 1198 and 1285cc capacities they moved further from those 2001 roots. The final version of the firm’s big twin was the 1260 DVT unit used in the Multistrada adventure machine and Diavel cruiser.

That added variable valve timing to the mix, reducing emissions and giving a healthy boost to torque and power.

Honda CB500 twin

This lightweight Honda unit is proof that a great engine doesn’t need to be a fire-breathing monster. The Honda CB500 engine might not win any GP races, but it sells by the truckload across the world, powering naked roadsters, sports bikes, adventure tourers and even a retro custom.

The CB500 name itself is laden with heritage, from the ancient CB500 four-cylinder motor of the early 1970s to an air-cooled twin in the mid-1970s before the big H released a whole new 499cc design in 1993.

That was a solid performer: fuelling was by carburettors, but with four-valves per cylinder, DOHC and water-cooling. It made 57bhp and was a commuter/despatch rider stalwart, and featured in the CB500 Cup race championship.

Euro2 emissions regs killed that motor in 2007, and it took a while for Honda to replace it with the current lump in 2013.

The latest 471cc twin is a total redesign, with a square bore/stroke ratio (67mm x 66.8mm), DOHC eight-valve head and fuel injection, which actually makes 10bhp less than the 1990s variant, to meet the European A2 licence 47bhp limit. It’s much cleaner and more economical, and makes its power lower down, so works almost as well on the road.

In the CB500X it makes a great lightweight adventure tourer, while the CBR500R is a solid novice sportsbike, and has had its own one-make race series across the world. A quiet, no-fuss hero to a generation of new riders and lightweight machinery fans.

Kawasaki ER-6 twin

Kawasaki’s 650 twin has two sides to its character. Originally launched in the ER-6n and f roadsters, it then appeared in the Versys 650 soft dual-sports machine, and did good work as a steady, 70bhp-ish roadbike engine.

There’s nothing ground-breaking about the tech: it’s a water-cooled, fuel-injected 649cc parallel twin, with four-valves per cylinder and DOHC head. But it produced grunty, usable power, and was a big hit in the class, matching the likes of the Suzuki SV650 and Honda Hornet for fun and practicality.

The other side to the ER-6 engine is, amazingly, its race career. The Minitwins race series grew up from the grass roots as a cheap, accessible club racing class, using the Kawasaki 650 and Suzuki SV650 engines. That grew into the Supertwins series that allowed more extensive tuning, and has turned into one of the most exciting classes at the Isle of Man TT races.

First run in 2012, the Lightweight TT class sees riders like Michael Rutter and Peter Hickman, do battle on tuned 100bhp racebikes based on the humble Kawasaki 650 twin.

The engine was tweaked to meet Euro4 rules in 2016, losing a couple of bhp, before being completely overhauled in 2020 to meet Euro5 rules. This latest engine powers the Z650, Ninja 650, Versys 650 and the cruiser-styled Vulcan 650 S, in the same unfussed, easy manner it’s been doing since 2005.

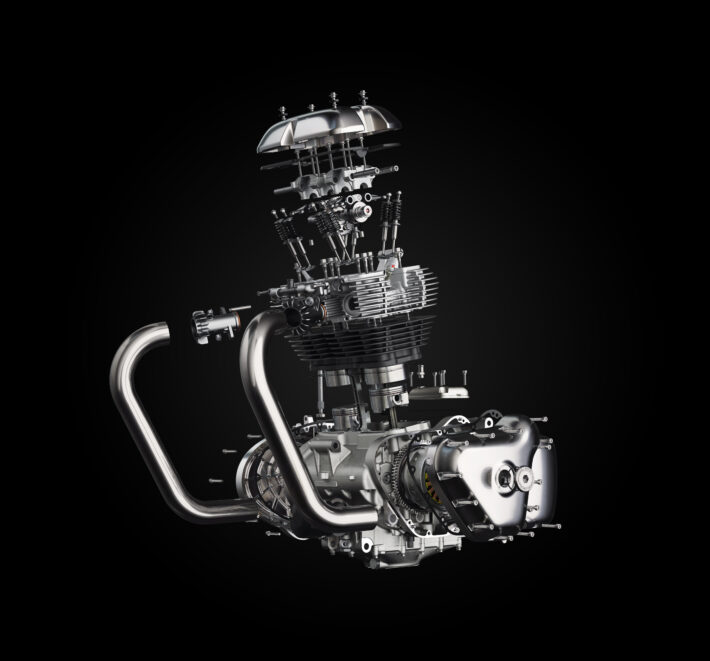

KTM 690 single

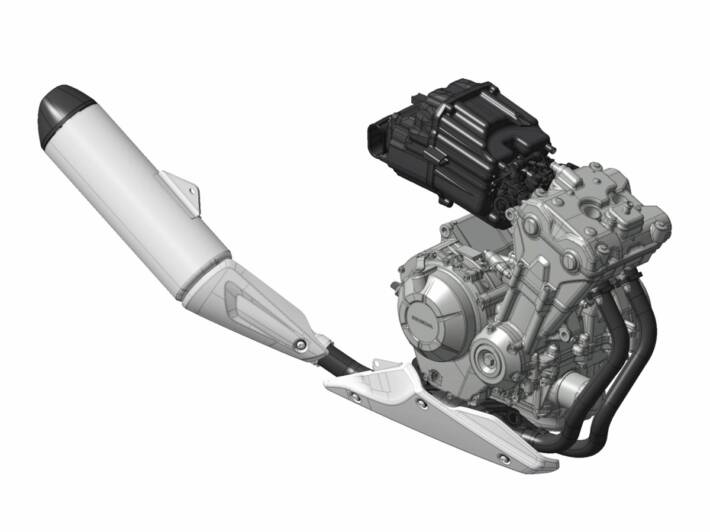

Like KTM itself, this excellent single-cylinder motor has its roots in the off-road world, going back as far as 1994 and the Duke 620 supermoto. Since then, the Austrian thumper has evolved into a super-strong, reliable, advanced powerplant, making 73bhp in its latest LC4 690 guise, and powering machines as diverse as the KTM 690 SMC, 690 Enduro and Husqvarna Svartpilen 701.

The most recent layout is pretty standard: four-valve head, water cooling, fuel injection, and there’s a single overhead cam with finger followers for the inlets and a rocker arm for the exhaust valve.

The 690 has a massive 105mm bore with super-short 80mm stroke, but the enormous forged piston is super-light, matched to a top-quality conrod.

What’s a bit unusual is the balancer system – obviously very important on a single, where there are no other pistons moving to balance against. The KTM 690 has a balancer shaft in the cylinder head, where you might expect a second camshaft, and there’s also another balancer shaft located more conventionally ahead of the crankshaft.

This optimised setup allows KTM to run higher revs on the 690, producing more power. Peak power is at 8,500rpm and the redline is at 9,000rpm, impressive numbers for sure. It’s the most powerful single cylinder bike engine you can buy – and a corking powerplant across the board.

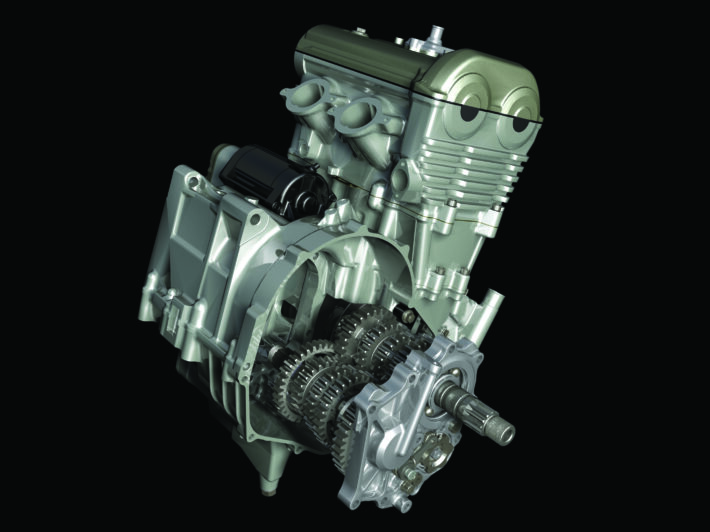

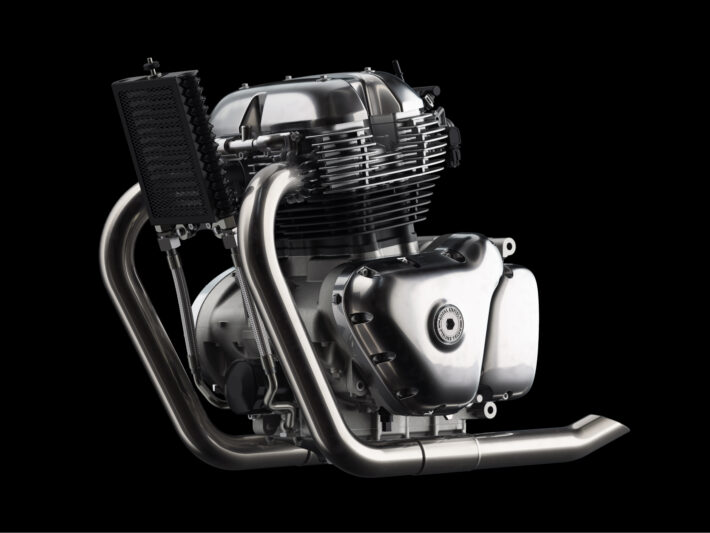

Royal Enfield 650 twin

Up until fairly recently, Royal Enfield’s engine tech was all pretty dated, with units that hadn’t changed much in decades. But in 2017, the firm unveiled its next generation of motors, the new 650 parallel twin, initially available in the Continental GT and Interceptor machines, and now in the Super Meteor cruiser.

It’s by no means a high-tech or complex unit. It’s air-cooled, with a single overhead camshaft, and puts out just 47bhp. On the plus side, it has four valves per cylinder, has a balancer shaft to counteract the vibes, and comes with a decent-sized oil cooler to assist the air-cooling fins.

It’s also a robust design: looking at a disassembled unit at the launch in California, you could see that there’s plenty of scope for expansion in the form of larger bores and longer stroke. The bottom end looks like it could easily handle much more in the way of torque and power, giving the firm an easy upgrade path for the future.

At the moment though, the 650 twin is just a nice engine to live with. It’s no fire-breather, but has a fabulously smooth and willing power delivery, ideal for the retro roadsters it lives in.

It’s economical, clean, and even looks good: the finned cylinders, polished cam cover and shapely casings echo the firm’s past while looking forward to the future. Nicely done.

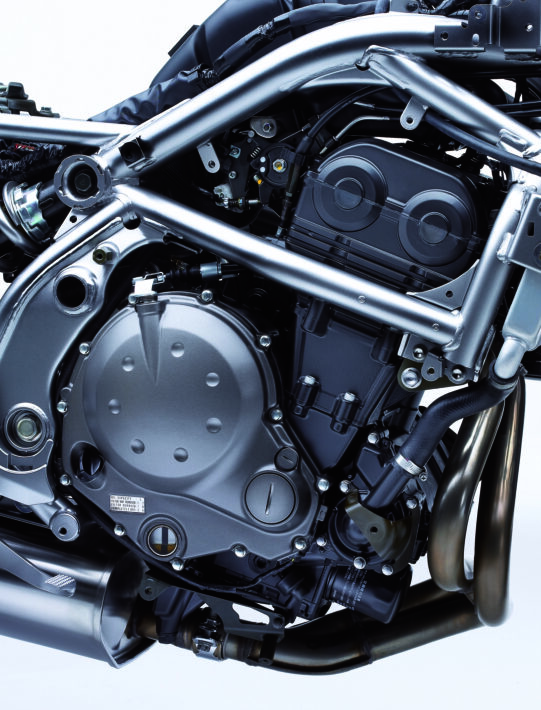

Suzuki GSX-R1000 K5

Suzuki’s the smallest of the Japanese bike makers, so has to make its engine designs go that bit further. And it’s certainly got its money’s worth out of this design – the 2005 GSX-R1000 motor. It was the first of a new generation of superbike powerplants – and the best of the crop when launched, with superlative power, torque and throttle response.

There was nothing revolutionary about the design: it had the same inline-four layout, with flat-plane crankshaft, 16 valves, DOHC and water-cooling as every other mainstream litre sportsbike.

But it was arguably the peak of Suzuki’s GSX-R engine design, and benefitted from lots of little advances – titanium valves, forged pistons, a wider bore and shorter stroke for a full 999cc capacity, special chrome-nitride piston rings, higher compression ratio – the list went on and on.

Add in Suzuki’s SDTV dual throttle valve fuel injection with twin injectors, the SET exhaust valve setup and a smarter ECU and you had a solid package.

The K5-K6 engine ruled, before the GSX-R1000 K7 and K9 upgrades fell off the pace a bit. Tighter emissions rules held development back, and Suzuki was behind the curve in terms of electronics too.

By 2011 the GSX-R was at the back of the pack – but the K5 engine found a new lease of life, powering the GSX-S1000 roadster and (later) the new Katana model.

Retuned for a less frantic life, the K5 engine does great work in this budget package, and has coped well with being cleaned up for Euro4 and 5 emissions. Still on sale in 2023, it certainly earns its spot as one of Suzuki’s great motors.

Triumph 675 Triple

Triumph wasn’t always a hardcore triple maker. At its launch in 1990, the new Hinckley machinery had a mix of inline four- and three-cylinder options, and in 2000 it added the TT 600 four-cylinder supersports platform. But as the 2000s rolled on, the firm concentrated on the triples (and twins for the retro Bonneville range).

This engine changed everything though. The 2006 Daytona 675 took on the best of the Japanese 599cc inline-fours, and beat them on road and track, mostly thanks to its superb engine. It plotted an enthralling path between the screaming fours and the thumping Ducati 748/749 V-twin, giving the best of both worlds.

It had stonking low-down grunt for such a small, high-output powerplant, while matching the fours on peak power, putting out a claimed 123bhp.

There’s nothing exotic about the 675 design: it’s an inline-three with 120° crank, four valves per cylinder, DOHC, water-cooling and a very oversquare bore and stroke (76×49.6mm). But it makes its torque and power lower down than the 599cc fours, and the result is a much more satisfying, character-laden powertrain.

The Daytona didn’t get to keep the motor to itself though: Triumph released a naked version the following year – the Street Triple. It had a slightly retuned engine that made less peak power, down to 107bhp, but with more midrange shove.

It was an instant, massive hit for Hinckley, and the 675 motor stayed on top for more than a decade, before being replaced by the 2017 Street Triple 765.

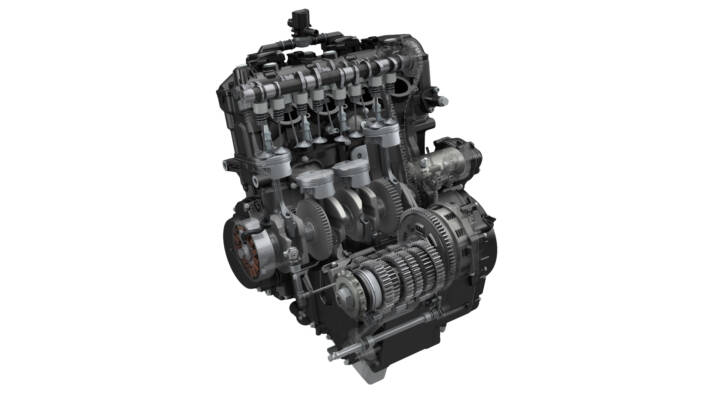

Yamaha R1

Yamaha’s original 1998 R1 engine was a revolution in terms of power, weight and packaging, with a focus on compact, lightweight design that still put out class-leading power. But it’s arguably the later ‘big bang’ R1 motor which is most interesting.

Launched in 2009, with the design borrowed from Yamaha’s M1 MotoGP machine, it switched from the even power pulses of a flat-plane crank to the uneven delivery of a crossplane crank. On the previous conventional design, the outer and inner pairs of pistons moved up and down together, so every 180° of crank rotation saw two pistons at TDC, with one firing and one on the exhaust stroke.

That meant there was an identical gap between each power pulse, giving a smooth delivery and screaming top end sound. The cross-plane crank has the big-end crankpins arranged at 90° from each other though, meaning there’s an uneven spread of power pulses and a ‘big bang’ sound.

The result is more mid-range grunt, and better drive out of the corners (though if the improvements were so clear you may wonder why Yamaha’s the only firm to have gone down this path). Yamaha managed to maintain peak power as well, putting out a class-matching 180bhp.

Since 2009 the R1 engine has gained electronic rider aids (in 2012) and in 2014 it was revamped with a new shorter stroke layout that bumped power up to nearly 200bhp. The crossplane crank motor has also been used in the excellent MT-10 super-naked, where its grunty nature and superb sound are right at home.

One comment on “Top 10 Motorcycle Engines”

I know it doesn’t really suit the article but what about Honda’s Cub range? Powering the most successful automotive vehicles of all time by a massive margin, which of us has not, at some time, either owned or ridden one?

See pictures from the Far East of them carrying whole families or being used as beasts of burden. That power unit surely deserves a mention in any list of the greatest bike engines.