Your dedicated guide to classic motorcycles…

Bored of new metal? Looking to relive your youth? You’re not alone. More and more riders are switching to older, classic bikes, rather than just signing up for a PCP deal on the latest high-tech megabike.

The reasons are manifold: maybe you don’t want electronics interfering with how you ride or perhaps the battle for ever more horsepower doesn’t appeal. You might even just prefer the looks of older machines – and modern retro reproductions aren’t quite the same, are they? Whatever the reasons, there are plenty of great choices open to you nowadays, on a sliding scale of convenience and authenticity.

Broadly speaking, the further back you go, the more compromises you’ll make in everyday riding. We’ve been spoiled in recent decades by electronics which simply work, tyres which grip, brakes which stop, engines which rev… you get the idea.

So if you’re expecting to buy a Triumph Bonneville from the 1960s which will work as well as one from 2018, you’re going to have to re-calibrate your expectations. On the other hand, plumping for a Kawasaki Z1000 from the 1980s, say, will give a dynamic experience that won’t quite match a 2018 Z1000 – but is far closer than the sixties machine. And with some careful tweaks and mods, you can bring the performance of older bikes much closer to modern stuff.

Old British Bikes

For most folk nowadays, when we think of a ‘classic bike’ this is probably what comes to mind. An old Norton, Triumph or BSA, with modest performance, slightly ropey electronics, yet really satisfying styling. There’s a basic choice between four-stroke singles and twins really – all air-cooled, with two valves per cylinder, generally operated by pushrods.

There are the odd standouts – Ariel’s square four, Scott two-strokes, BSA Trident triples – but 90 per cent of what you’ll be looking at are singles and twins. If you’re getting into the classic scene for the first time, it makes sense to keep things fairly mainstream. Sticking to the big three of BSA, Triumph and Norton will make life easier when you need to find parts, advice, specialist servicing and the like.

Deciding that you’re going to make a life’s hobby from riding pre-war Rudges is admirable, but likely to end in frustration at times… Here’s our choice of the British classics to have a look at.

BSA Gold Star

The Gold Star was the race replica of its day just after WW2, with an alloy 350 or 500cc single cylinder motortuned to a fairly high level. Indeed, the ‘Gold Star’ moniker comes from its victory under Wal Handley at the pre-war Brooklands circuit, where a gold star was awarded to riders who managed a 100mph lap.

Built between 1938 and 1964, it was the choice for TT racers in particular, and the Goldie won a shedload of Junior and Senior TTs in the 1950s. High compression pistons, racing carburettors, stronger bottom ends – there were plenty of tuning options. Even as stock, each engine was essentially hand-finished from the factory, and came complete with individual dyno sheets showing the actual power output.

Capable of a then-impressive 90mph, BSA actually told owners that the Gold Star was specifically designed for competition use, and wasn’t suitable for use as a touring bike. That was a big thing in the post-war era, when most motorbikes were used as the only transport for working folk, often with a sidecar attached.

Towards the end of its lifetime, the Gold Star was restricted to offroad, or ‘scrambler’ builds, and its ‘non-unit’ engine with separate gearbox marked it out as rather old-fashioned. It was replaced by the BSA B50 with a combined ‘unit’ engine and gearbox powertrain in 1970. Nowadays, there are still a few Gold Stars around, though original mint condition ones will be costly. They definitely have the proper 1950s classic look and feel though.

The original ignition system used a magneto rather than a battery and coil, so unless it’s been replaced, be ready to read up on tuning this setup. Alongside that, the racing tune of the engine means things like a steady idle and easy hot starting are often hard to achieve. But upgrading the ignition and fuelling with modern parts will definitely pay dividends.

Drum brakes will be a revelation (of the bad kind) for modern riders used to discs, but again, careful setup with modern parts can sharpen up the performance markedly. New cables and fresh friction linings, with remanufactured brake drums can make a big difference.

Triumph Bonneville

This is perhaps the definitive British classic bike – and with more than 300,000 of them made throughout the 1960s and 70s, one of the most common still around. The name comes from the Utah salt flats of course, where a Triumph-powered streamliner 650 twin called ‘Devil’s Arrow’ topped 214mph in 1956 with Texan racer Johnny Allen at the controls.

Allen’s race-tuned, methanol-burning engine was based on the motor from the Tiger T110, which had a single carburettor as standard. Twin carbs allowed more peak power, so while the production Bonneville stuck with the same 650cc pre-unit engine as the T110, it gained an extra carburettor, giving a claimed 46bhp instead of the Tiger’s 42bhp.

Aimed primarily at the power-hungry, wealthy US market, the new Bonneville T120 was launched at the Earl’s Court London bike show in the autumn of 1958. A new ‘unit’ engine with the gearbox and engine combined into one powerplant appeared in 1963, which allowed a new single-tube frame design. That, plus other mods, gave big handling improvements, and over the next ten years, the 650 Bonnie continued to develop in terms of power and handling.

There was change on the horizon though. Honda had launched its CB750 superbike in 1969, and with its 68bhp, inline-four engine, disc brakes and electric start, it instantly made the rest of the market look a bit lame. Triumph had to respond, so for 1973, it came up with the T140 – a full 744cc 750 Bonneville, with a big bore engine, more torque and a few more peak bhp as well, up to 49bhp from 46.

Sadly, the British industrial relations woes of the 1970s struck, and whether you blame lack of investment, poor management or recalcitrant shop stewards, Triumph as a mainstream bike maker disappeared, until the early 1990s. The Bonneville kept going in cottage industry form, hand-built by Harris, until John Bloor’s Nü-Triumph kicked off again in Hinckley in 1992. The modern Bonnie appeared in 2001, with a totally new 790cc parallel twin engine, that later expanded to 900 and 1200 forms.

Norton Commando

Like the Bonneville, this is one of the best-known of the old British bikes. Having said that, I started riding in the late 1980s, and there weren’t really very many on the roads by then.

Again, like the Bonneville, the Commando was based around a rather low-tech engine – an air-cooled twin with two valves per cylinder, worked via pushrods by cams mounted down by the crankshaft. In some ways, the motor is an even older design than the Triumph, using a pre-unit powertrain with a separate gearbox and external primary drive. The frame was a bit better, with a new design that rubber-mounted the engine, to try and isolate the massive vibrations from the unbalanced twin, but this ‘Isolastic’ system was tricky to maintain and set up properly.

Despite all that, the Commando did well in terms of sales during its short life. Launched in 1967, it continued as a 750 until 1973 when it was relaunched as an 850.

The specification improved, with electric start and better brakes, but by then the bigger picture was looking grim for Norton. The firm eventually collapsed, with the last bikes being produced in 1977, and though several firms aimed to continue the brand, the Commando was finished as a mainstream machine.

Japanese Classics

Yes, I know, the 1970s were only about 25 years ago. Weren’t they? Ah. Time flies, and early Japanese bikes definitely now fall into the classic category, especially for riders aged in their 40s, 50s and 60s. The very first Japanese bikes are pretty rare now – things like the Honda 250 Dream of the 1960s, or a Yamaha YDS-3 250 two-stroke from 1964 didn’t sell in large numbers, so are unlikely to pop up on your local Gumtree site. No, it’s bikes from the mid 1970s-on which are likely to make good classic buys. Here’s a few we’ve picked out for you…

Kawasaki Z900/1000

The original Z1 was planned as a 750, and just missed being the first superbike, pipped to the post by Honda’s 1969 CB750. So the design team pulled their launch, and made some serious improvements. And when the Kawasaki appeared in 1972, it was definitely the better bike.

More power, from a ‘proper’ 903cc DOHC engine rather than the Honda’s SOHC unit, with better brakes and chassis, the Z1 kicked off Kawasaki’s period of four-stroke domination through the 1970s and 80s. A super-strong engine, with loads of tuning potential, it evolved into the Z1000, then GPz1100 before the water-cooled 16-valve engines took over with the GPZ900R in 1984. Nowadays, a big-four Kawasaki makes a lot of sense.

There’s plenty of tuning options for engine and chassis, and even as stock, they work pretty well even compared with today’s bikes. A GPz1100 was my dream bike as a 13-year-old kid, and one day I’ll finally get one of my own…

Kawasaki Two-Stroke Triples

Tankslapping about at the other end of the practicality scale are Kawasaki’s various two-stroke triples. Available in 250, 350, 400, 500 and 750cc flavours, from the late 1960s until 1980, all had loose handling, light-switch power delivery and ropey reliability. You’ll need to be fairly serious, and have shares in a piston factory to make much sense of this. But then bike-buying decisions are seldom sensible!

Honda

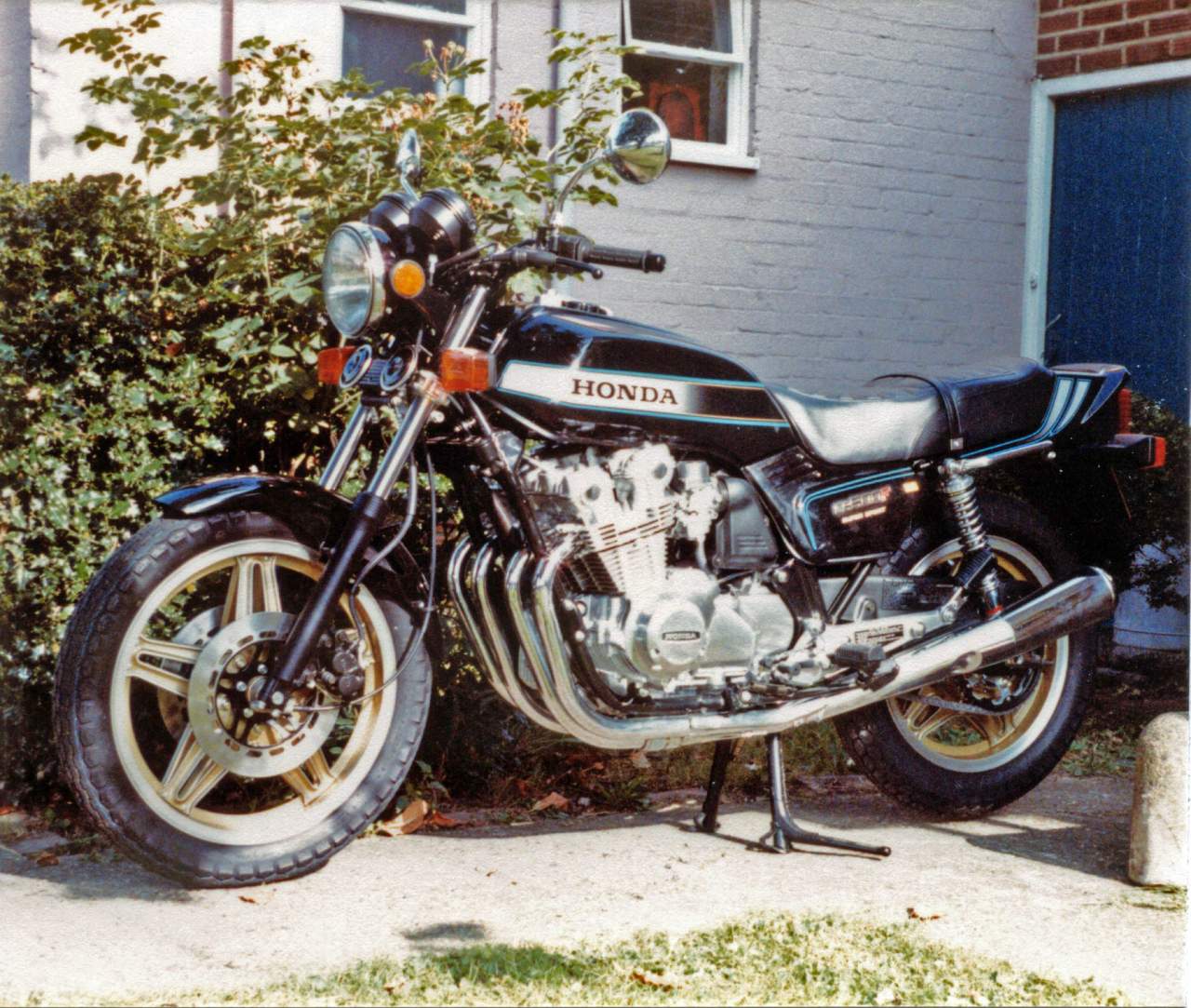

Back in the 1970s, Honda’s range of four-stroke inline ‘CB’ machines covered all the capacities, from 125s up to 1100s. So there’s plenty to choose from. They were also built pretty well, so have lasted better than some other options… The big boss of the firm, founder Soichiro Honda wasn’t a big fan of two-strokes, so the firm avoided them wherever possible, meaning they didn’t build any crazy strokers like Kawasaki and Suzuki did.

The CB750 is a solid, if steady option as a practical classic. Early models are too pricey and collectable for our purposes, but later 1970s bikes are worth a look. The later DOHC models from the 1980s, and the derived CB900F look good and work well enough, though they originally had camshaft troubles. Any still running now should have been sorted with Honda’s revised parts though.

Suzuki

Much like Kawasaki, Suzuki made a solid range of inline-four four-stroke bikes, as part of the ‘UJM’ – Universal Japanese Motorcycle trend of the time. The GS models came in smaller capacity twins – 250, 400, 425, 450 and 500, and larger-capacity inline-fours: 550, 650, 750, 850, 1000 and 1100. The GS1000 in particular had an immensely strong bottom end, with roller crankshaft, and loads of tuning potential. A tidy example of a GS1000 or 1100, or the later GSX 16-valve versions, can make a bruising streetbike, with loads of torque, decent old-school handling and handsome styling.

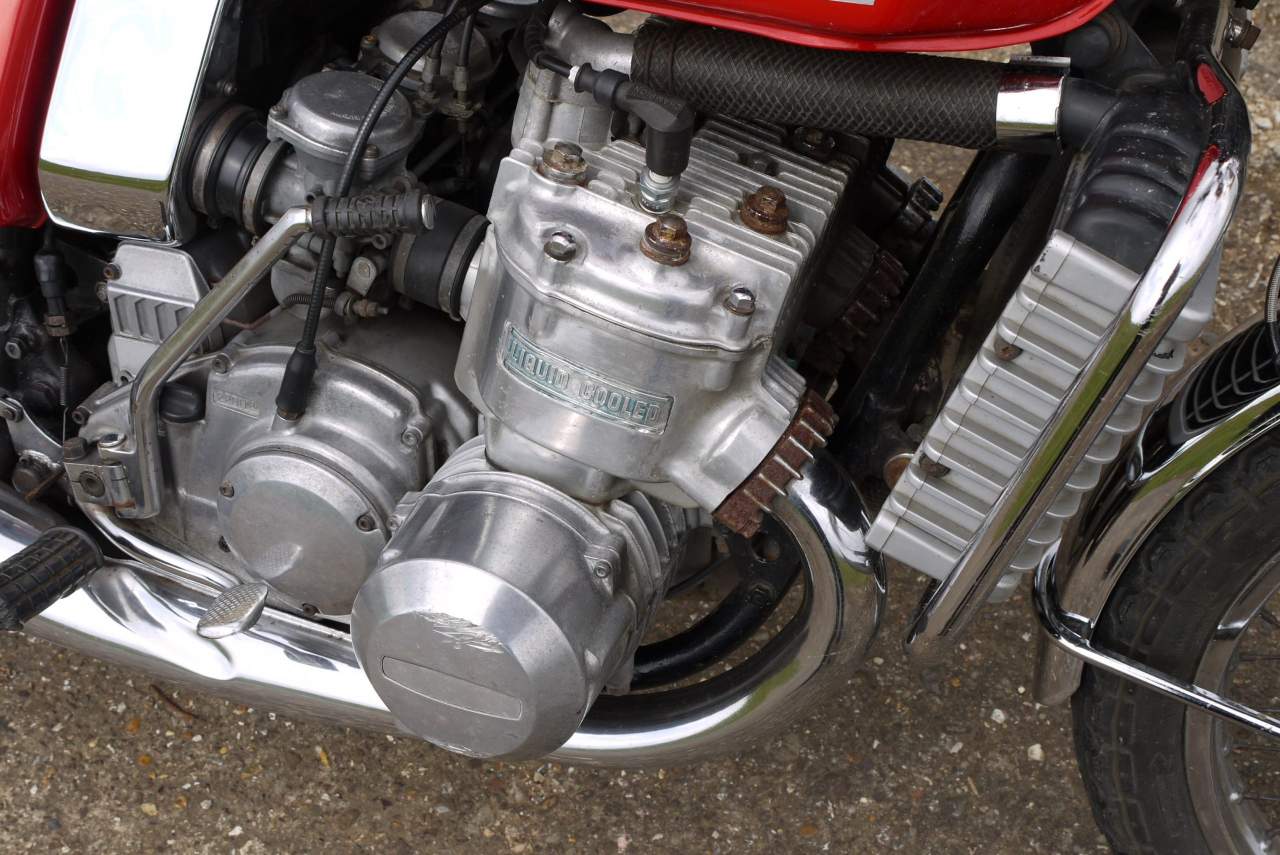

Suzuki Two-strokes

Suzuki’s 1970s two-strokes were a bit tamer than Kawasaki’s – the 1971 GT750 had a water-cooled engine (a first for a Japanese bike), and was intended as a tourer rather than a fire-breathing race-rep. The smaller GT380 triple was also pretty steady, while the GT twins – 250 and 500 strokers – had a bit more go about them, albeit in a rather outdated package. The ultimate Suzuki two-strokes are the later RG250, RG500 and RGV250s though. These bikes, from the 1980s, had high-tech, high-powered engines in solid chassis designs.

The parallel twin RG250 of 1983 was the first production bike with an aluminium frame, while its ‘deca-piston’ brake setup was miles ahead of the competition. The front brakes had twin four-piston calipers, and the rear was a twin-potter, giving a total of ten brake pistons – amazing when most bikes had one per caliper.

The motor put out around 40bhp, and it was a light, lively little race replica. The later RGV250 switched to a V-twin engine, made 65bhp and was a fabulous performer in 1988. Launched a couple of years after the 250, the RG500 had a slick square-four two-stroke engine that used disc-valve induction, in a similar aluminium chassis to the 250.

Suzuki claimed 95bhp from the engine, but 80 was nearer the mark. That sounds a bit tame these days, but back in 1985, it was a fearsome tally, especially in such a light machine (175kg wet). The RG strokers are very much in demand these days – the appeal of the long-gone two-strokes runs deep and they’re still decent performers. As a result prices are high – but on the other hand there are quite a few of them about still, and there’s a small cottage industry rebuilding engines and providing replacement parts for them still.

Yamaha

Yamaha also put a lot of effort into its two-stroke machines in the 1960s and 70s, and the firm arguably had much more success than the competition. Its RD twins ranged in capacity from 125 up to 400cc, and went from air-cooled piston ported engines, through to water-cooled reed valve motors, then finally the famed ‘Yamaha Power Valve System’ YPVS designs.

Each of these developments wrung more and more power and reliability out of the basic two-stroke twin design, and the final RD350 YPVS design is one of the all-time classic bikes. As a practical classic, something like an RD 400 looks good, works well, and has decent performance. The later RD350s are becoming harder to find, and prices have risen, but there are still some decent ones to be had out there.

The ultimate RD is the RD500 LC – a V-four GP500 replica, like the Suzuki RG500. These didn’t sell in big numbers, and are becoming exceedingly rare, with sky-high prices to match.

European Classics

Bored by the Brit bikes? Jaded by Japanese jollies? Then you need some Euro-classics. The big names like BMW, Moto Guzzi and Ducati were making some decent bikes back in the 1970s and 80s, while now-defunct firms like Laverda were much bigger. Here’s our pick of the alternative classic options from ‘The Continent’, as 70s Brits called it…

BMW

The Bavarian Motor Works’ Boxer twins have been going since the 1920s of course, and if you’re really keen, then you can hunt around for an R32 from back then. Good luck! The Second World War obviously got in the way, and it was 1950 before BMW bikes were properly back in production. The R25 250cc single got them going, then the 500 R51 and 600 R67 Boxer twins appeared. It was the 1970s when BMW really cranked up its designs though. The flagship R90S made such an impression that the firm celebrated it recently with its RnineT modern retro range.

It was a full supersport machine at the time, with nosecone fairing, 120mph performance and actually won superbike races at Daytona, and the first AMA superbike championship, ridden by British racer Reg Pridmore. The air-cooled Boxers of the 1980s and 90s make good everyday classics, though the styling isn’t to all tastes. Later Boxers, and the K-series of laid-down triples and inline-fours have a certain charm – but again, the curious modernist looks will put many off.

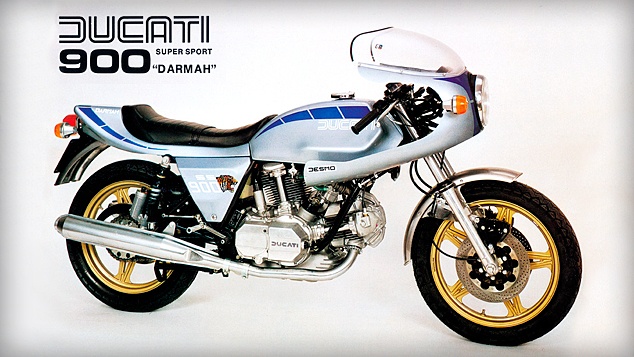

Ducati

Early Ducatis from the 1950s and 60s offer some interesting engineering, including desmodromic-valved single cylinder racers and a monstrous V4 prototype. It’s the V-twins that we’re here for though – the desmodromic machines which led to the superbikes of today.

A 1970s 900 Supersport was light and powerful for the time, and thought the build quality and reliability would make you cry nowadays, back then, it was all worth it for the performance and style. You’ll need a load of skill, or a good garage to keep one of these going as a daily runner these days, but if you can manage it, you’ll enjoy a really unique riding experience.

Moto Guzzi

Perhaps the marque (along with Harley-Davidson) which has stayed closest to its roots, the Guzzi of today isn’t that far off the bikes from the past. A transverse V-twin, with air-cooling and shaft drive, the likes of the Le Mans and the S3 were the superbikes of their days in the 1970s. High-spec chassis parts and decent engine performance made for sporty touring machines, albeit with then-typical Italian reliability.

Nowadays, the Guzzi look is bang-on trend, and there’s a decent aftermarket backing up the older machines. They’re simple enough, which is in their favour, so stuff like forks, shocks, brakes and wheels are easily maintained or upgraded. Ditto the engines – as ever more modern electrical components will make a big difference to daily running.

Top Tips to Running a Classic Bike

So, now you’ve had the lowdown on the major players in the Classic bike market, and we’ve been to Japan and back on our quest, it’s time to find out how to keep these vintage machines running! Check out our top tips to running a Classic bike…

Tyres

Of all the developments in recent decades, tyres have to be amongst the most important – if often unsung heroes. It might be a bit of a cliché to say they’re the only thing keeping you on the road, but remember what they say about clichés. The grip provided by modern tyres, especially in cold, wet conditions, is nothing short of amazing.

Now, riding a classic bike means using classic tyre sizes – and they don’t always come in the most modern tyre models. Older bikes from the 1960s and 70s will often use imperial-sized rubber like 3.00 x 18. That’s a three-inch wide tyre on an 18-inch diameter rim, with a 100% aspect ratio – the tyre sidewall is also around three inches high.

Modern metric sizes use millimetres for the tyre width, but stick with inches for the rim diameter – so a 100/90 18 tyre is 100mm wide, with a sidewall height 90% of the width – 90mm, obviously – and will fit an 18 inch wheel.

Luckily, several of the big bike firms still make the old sizes – and of course, they use modern manufacturing methods and materials. That’s obvious when you think of it – they wouldn’t use rubber and nylon ply materials from the 1960s would they? So while performance is a little down on wide, modern radial-ply tyres, the old-school tyre sizes you buy today work far better than the originals from the 1960s, 70s and 80s.

We like the classic tyre fitments from Avon and Metzeler, while Dunlop, Bridgestone, Michelin, Pirelli and Continental also make decent options in classic bike sizes.

Ignition

If you remember riding bikes in the UK before about 1990, you probably also remember that ignition faults caused no end of headaches. HT ignition cables, coils, CDI units all gave problems, mostly because the wet weather in Britain got inside unsealed electrical connectors, causing corrosion and misfires. From the mid-1990s-onwards, firms started to use much better connectors, with built-in seals, and bikes got much better at starting and running.

Going back further than the 1980s, bikes would often use contact breaker or ‘points’ ignition systems, where a rotary switching mechanism created the spark, usually with mechanical advance-retard gizmos that used springs and weights to adjust the spark timing.

Points were fine when they were working, but needed regular checks to keep the correct contact breaker gap and timing, and were susceptible to moisture, corrosion and mechanical wear causing poor running. Nowadays, you should be able to replace the contact breaker system with a more advanced electronic setup, using optical or magnetic sensors which are largely weatherproof and maintenance-free. Definitely recommended if you’re looking to run an older bike day-to-day.

Electrics

The same problems that afflict ignition systems affect the rest of an older bike’s electrics too. Luckily they don’t have too much – but you’ll still need decent lights and working indicators. Checking and replacing corroded connectors or poorly bodged wiring repairs will sort a load of problems, and swapping in modern bulbs (maybe even LED units) and an up-to-date battery will also help.

Some classic bikes use a six volt electrical system, which is much less useful than a 12 volt setup. It’s possible to upgrade to a 12v system, but you’ll need to replace the alternator/generator, regulator/rectifier charging circuits, battery, lights and horn, plus the ignition system. A fairly big job, but well worth it as part of a major rebuild.

Brakes

There are two main problems with older brake systems – weak drum brakes and early disc brakes, which are terrible in the wet. Modern pads and alternative disc materials can sort the latter problem, while good maintenance can work wonders on drums.

Careful lubing and adjustment of cables and cam lever arms, fresh brake shoes and new inner drum surfaces will all help get the best out of your brake drum setup. On later Japanese classics, you might be able to upgrade calipers and other components with parts from later bikes. For example, the six-piston Tokico calipers used on some Kawasakis and Suzukis in the 1990s can seize up and generally give weak performance.

The four-piston Nissin calipers used on Suzukis and Triumphs of the era fit straight on and provide much better stopping power.

Suspension

The original suspension on old bikes is not great on two fronts: it wouldn’t have been that great to start with, and over time, the internal damping oil breaks down, resulting in poor performance all round. With front forks, fitting uprated springs and changing the oil for a slightly heavier weight can often improve matters on old damper-rod forks. Replacing with newer cartridge style units might also be an option worth exploring.

With rear dual shocks, simple replacement is usually the best option. New-old-stock shocks can be tracked down if you want to keep your old Z1000 looking standard, or you can opt for a high-performance upgrade in the form of some Öhlins or similar units.

Firms like Hagon produce very decent standard shocks at a good price if all you need is something that works well and looks okay. Ditto with monoshocks, on bikes more than about ten years old, the original parts will be very tired, so an upgrade will pay dividends.

Companies like Öhlins, Nitron and WP all make aftermarket shocks which are rebuildable and serviceable, so if you can find a used one for an older bike, a proper service centre will be able to bring the performance back to as-new. It’s also worth checking the swingarm linkages on old monoshock bikes: the bearings, bushes and seals all degrade over time. A full service with new bearings and loads of lovely fresh grease will totally transform a saggy back end…

What are your favourite classic motorcycles?

All images used have been in accordance with the Creative Commons Legal Code Licence and credited appropriately.